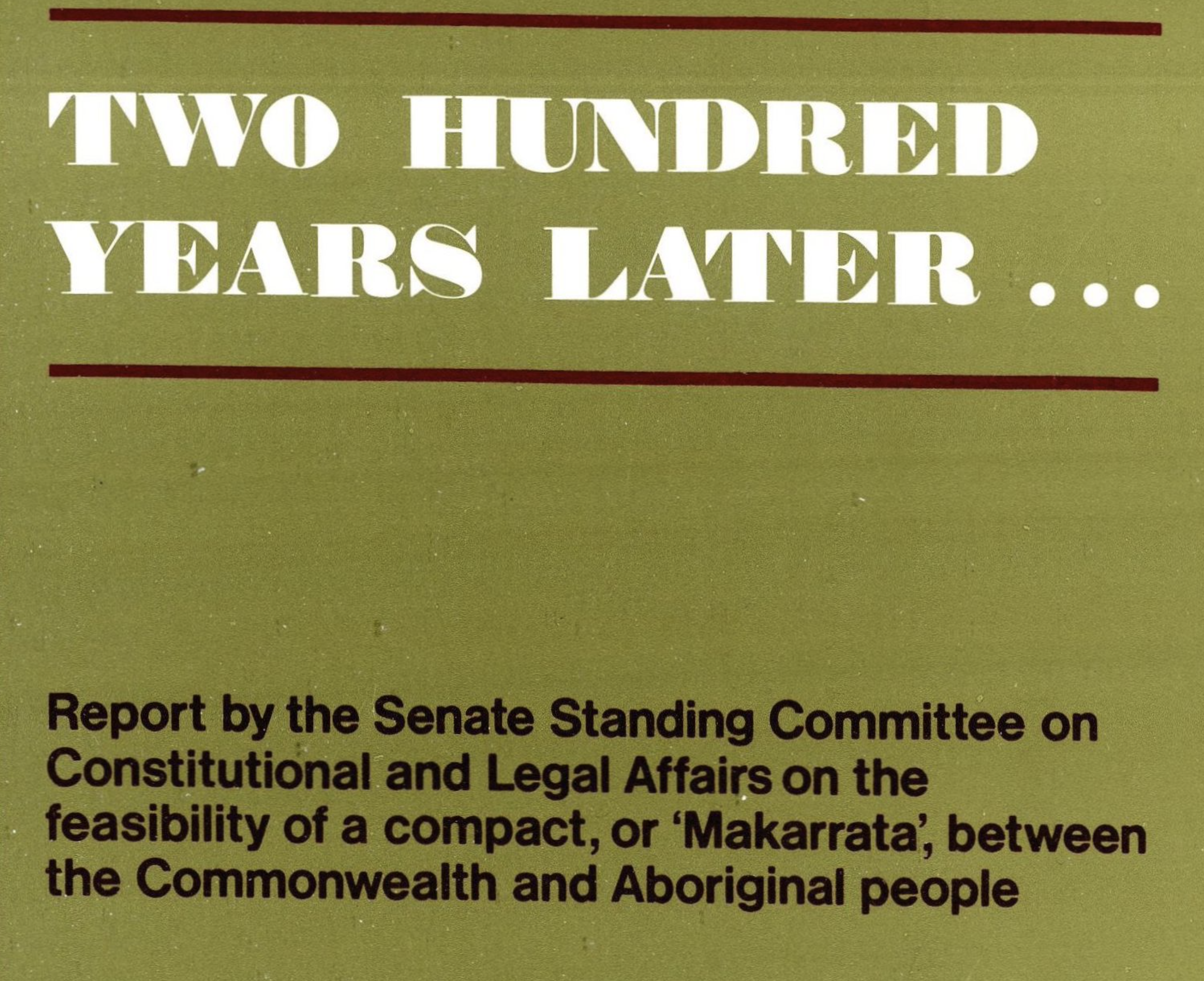

In 1983 a report known as the Constitutional and Legal Affairs on the feasibility of a compact or 'Makarrata! between the Commonwealth and Aboriginal people was presented to Parliament by the Chairman of the Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs (Senator Tate) , it is imperative every Australian read the report to be well informed on the current Voice to Parliament referendum.

The High Court in the past has considered section 51(xxvi), In Koowarta v. Bielke-Petersen and Others (1982) 39 ALR 417 and Commonwealth v. Tasmania (the Tasmanian Dam Case). In Koowarta the plaintiff, an Aboriginal, brought an action under the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) alleging racial discrimination on the part of the Queensland Government by virtue of its refusal to approve the transfer to him and other members of an

Aboriginal group of a pastoral lease acquired by the Aboriginal Land Fund Commission on their behalf. The refusal was based on Queensland Government policy which did not view favourably proposals to acquire large areas of additional freehold or leasehold land for development by Aborigines or Aboriginal groups in isolation. The Court examined the constitutional validity of certain sections of the Racial Discrimination Act and the plaintiff's standing to sue under the Act. Although the case turns on a majority view of the external affairs power (s.51 xxix), it nevertheless contains interesting comments on the scope of the races power. All members of the Court, with the exception of Murphy and Mason JJ, considered the placitum in some detail. Gibbs CJ, with whom Aickin and Wilson JJ agreed, considered the placitum to have a wide meaning, while Stephen J introduced some limitations on the potential scope of the power.

Gibbs CJ affirmed that the early purpose of the placitum had been to enable the legislature to control and administer influxes of foreign racial groups but that, in addition, after its amendment in 1967 and 1in its present form', the placitum empowered the Commonwealth legislature to pass laws 1prohibiting discrimination against people of the Aboriginal race by reason of their race.' Gibbs CJ then clarified some of the terminology used in placitum (xxvi). For example, the ambit of racial groups to which the placitum referred had not previously been considered, the only parameter being 1the people of any race.1 Gibbs CJ provided a narrower interpretation of the word 'any1, stating that it was used in the sense of 1no matter which1 and in the context of the placitum did not mean 'all1. He noted that it is not possible to construe par.(xxvi) as if it read simply 'The people of all races. The Chief Justice then explained that the method of identifying those racial groups to which the placitum could be applied is the qualification 'for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.'

The Parliament may deem it necessary to make special laws for the people of a particular race, no matter what the race. If the Parliament does deem that necessary, but not otherwise, it can make laws with respect to the people of that race. The opinion of Parliament that it is necessary to make a special law need not be evidenced by an express declaration to that effect; it may appear from the law itself. However, a law which applies equally to the people of all races is not a special law for the people of any one race.

It follows therefore that if the Commonwealth Parliament deems it necessary either by express declaration or by implication, it may make special laws for the Aboriginal people.

5.16 Like Gibbs CJ, Stephen J also concluded that placitum (xxvi) authorises the enactment of 1special1 laws. However, his interpretation of a special law differed from that of Gibbs CJ to the extent that he considered there was a requirement that there be in fact a necessity for special action before laws authorised by the placitum could be enacted. It cannot be that the grant becomes plenary and unrestricted once a need for special laws is deemed to exist; that need will not open the door to the enactment of other than special laws.

Although it is people of any race that are referred to, I regard the reference to special laws as confining what may be enacted under this paragraph to laws which are of their nature special to the people of a particular race. It must be because of their special needs or because of the special threat or problem which they present that the necessity for the law arises; without this particular necessity, as the occasion for the law, it will not be a special law such as s.51(26) speaks of. No doubt it may happen that two or more races will share particular problems within the Australian community and that this will make necessary the enactment of one law applying equally to those several races; such a law will not necessarily forfeit the character of a law under par. (26) because it legislates for several races.

Mr Gary Rumble, a lecturer in Commonwealth constitutional law at the Australian National University, in submissions to the Committee before and after the High Court's decision in Koowarta. concluded that the Commonwealth has sufficient power to enact legislation to carry out the sorts of undertakings likely to be the subject of a compact. In reaching this conclusion, he analysed, among other powers, the potential scope of section 5 1 (xxvi).

In his second submission to the Committee, in which among other things he discussed the High Court's conclusions on section 51(xxvi) in Koowarta. Mr Rumble noted the wide, though still largely undefined, powers over Aboriginal matters which the Court in that case appears to have guaranteed the Commonwealth Parliament. After quoting from Gibbs CJ's judgment, he commented:

That discussion suggests no significant restraint on the kind of laws that can be enacted under s.51(xxvi), but it does not say that the power is unlimited.

Later, in a summary of the Court's approach Mr Rumble stated:

Apart from Stephen J (and to a lesser extent Wilson J) the members of the Court in Koowarta did not indicate the limits to the kind of laws that may be enacted under s.51(xxvi) .

The limitation expressed by Stephen J was that s.51(xxvi) would only permit the Commonwealth to legislate to deal with an existing special need associated with a race. However, Mr Rumble considered that this limitation may prove to be of little assistance in determining the scope of the power:

This test would be unpredictable in its application and could therefore hinder Makarrata implementation. Large doubt, however, exists as to whether this test will be developed.

Mason J in the Tasmanian Dams case said that the power under s.51(xxvi) was wide enough to enable the Parliament

(a) to regulate and control the people of any race in the event that they constitute a threat or problem to the general community; and

(b) to protect the people of a race in the event that there is a need to protect them.

Subsequently, in answer to an argument that, as a subject of the legislative power, the cultural heritage of the people of a race is distinct and divorced from the people of that race so that a power with respect to the latter does not include power with respect to the former, Mason J stated:

The answer is that the cultural heritage of a people is so much of a characteristic or property of the people to whom it belongs that it is inseparably connected with them, so that a legislative power with respect to the people of a race, which confers power to make laws to protect them, necessarily extends to the making of laws protecting their cultural heritage.

This goes beyond the view taken by Stephen J in Koowarta in that it leaves it to the Parliament to determine whether the necessity for special laws exists, rather than requiring, as Stephen J appeared to do, that the need exists in fact. Stephen J's view was quoted by Mason J in the Tasmanian Dam Case (at p. 121) and must be taken to have his implicit support. Wilson J (at p. 174) and Dawson J (at p. 305) were of the view that it is for the Parliament alone to deem it necessary to make the law, although the Court must still determine whether the law answers the description of a special law.

5.22 Brennan J (at p. 220) inferred from the passage of the 1967 referendum that the primary object of the power under s.51(xxvi) is beneficial. He continued:

The passing of the Racial Discrimination Act manifested the Parliament's intention that the power will hereafter be used only for the purpose of discriminatorily conferring benefits upon the people of a race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws. Where Parliament seeks to confer a discriminatory benefit on the people of the Aboriginal race, par. (xxvi) does not place a limitation upon the nature of the benefits which a valid law may confer, and none should be implied.

Continuing his broad interpretation of the power, His Honour stated:

I would not construe par. (xxvi) as requiring the law to be "special" in its terms; it suffices that it is special in its operation.

By way of contrast to the characterisation as general rather than special laws, which Gibbs CJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ placed upon the provisions in question, Brennan J took the following view (at p. 224):

To confine the'legislative power conferred by par. (xxvi) so as to preclude it from dealing with situations that are of particular significance to the people of a given race merely because the statute on its face does not reveal its discriminatory operation would be to deny the power the high purpose which the Australian people intended when the people of the Aboriginal race were brought within the scope of its beneficial exercise.

Deane J said that the words 'people of any race1 have a wide and non-technical meaning and that the phrase is apposite to refer both to all Australian Aboriginal people collectively and to any identifiable racial sub-group among them (p. 255). His Honour stated that:

The relationship between the Aboriginal people and the lands which they occupy lies at the heart of traditional Aboriginal culture and traditional Aboriginal life ... one effect of the years since 1788 and of the emergence of Australia as a nation has been that Aboriginal sites which would once have been of particular significance only to the members of a particular tribe are now regarded by those Australian Aboriginals who have moved, or been born away from ancient tribal lands, as part of a general heritage of their race (pp. 256-57).

196 pages