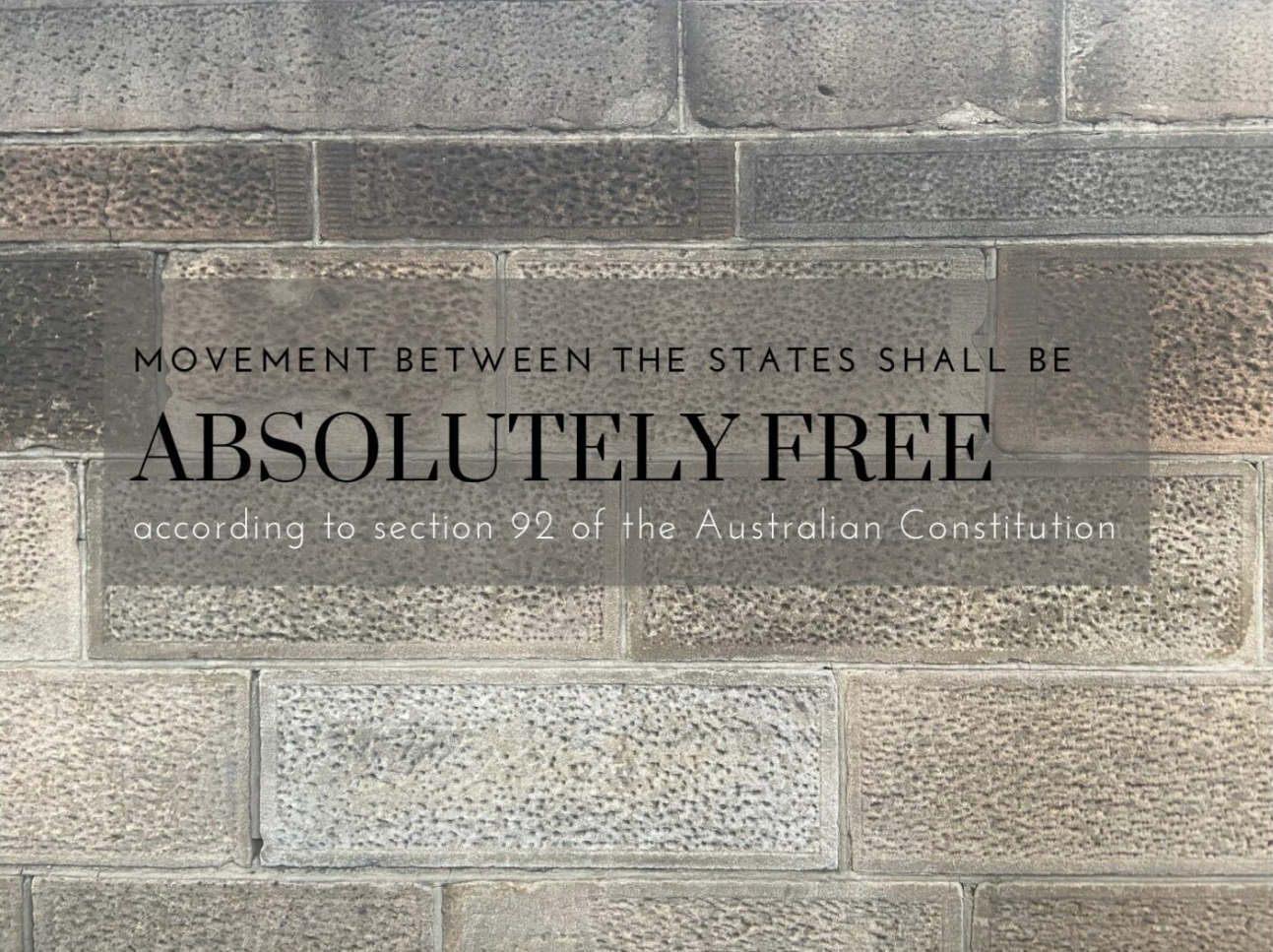

Can the States legislate to stop you crossing, independently the State Boundaries by exercising your personal right to do so guaranteed by the constitution? We then explore Cole v Whitfield in the journey of understanding of what section 92 brings to the individual

HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Latham C.J., Rich, Starke, Dixon, McTiernan and Williams JJ.

BANK OF N.S.W. v. THE COMMONWEALTH

(1948) 76 CLR 1

11 August 1948

43. Section 92 provides, so far as material, that trade commerce and intercourse amont the States whether by means of internal carriage or ocean navigation shall be absolutely free. We adhere to the opinion already expressed by Rich J. in Peanut Board v. Rockhampton Harbour Board (1933) 48 CLR 266, at p 277 and Williams J. in Australian National Airways Pty. Ltd. v. The Commonwealth (1945) 71 CLR 29, at pp 107, 110 that the freedom guaranteed by s. 92 is a personal right attaching to the individual. The same opinion has been expressed by several judges of this Court; see for instance O'Connor J. in Fox v. Robbins (1909) 8 CLR 115, at pp 126, 127 ; Higgins J. (1909) 8 CLR, at p 131 ; Isaacs J. in R. v. Smithers; Ex parte Benson (1912) 16 CLR 99, at p 113 in James v. South Australia (1927) 40 CLR 1, at p 32 and particularly in James v. Cowan (1930) 43 CLR 386, at pp 418, 419 (a judgment described by Lord Atkin in delivering the judgment of the Privy Council on appeal (1932) AC, at p 561; 47 CLR, at p 398 as a convincing judgment). In that case (1930) 43 CLR, at p 418 Isaacs J. referring to the expropriation of goods by a State, said: "The question is, how has the personal right of trading inter-State by the former owner been interfered with? That is a personal right, not a property right." In the Peanut Case (1933) 48 CLR, at p 288 Dixon J. said: "The provisions operate directly upon the individual grower's liberty of disposing of the peanuts he produces for sale." In O. Gilpin Ltd. v. Commissioner for Road Transport and Tramways (N.S.W.) (1935) 52 CLR 189, at p 211 Dixon J. said: "Trade, commerce and intercourse among the States is an expression which describes the activities of individuals. The object of s. 92 is to enable individuals to conduct their commercial dealings and their personal intercourse with one another independently of State boundaries." In James v. Commonwealth (1936) AC 578, at p 614; 55 CLR 1, at pp 43, 44 , Lord Wright, in delivering the judgment of the Privy Council, said section 92 may seem to be, "a constitutional guarantee of rights, analogous to the guarantee of religious freedom in s. 116, or of equal rights of all residents in all States in s. 117." He referred to s. 92 as "the declaration of a guaranteed right" (1936) AC, at p 631; 55 CLR, at p 59 . It is to be noted that His Lordship groups with s. 92 ss. 116 and 117, that the provision in s. 116 that no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth is an express personal guarantee, and that s. 117 is also an express personal guarantee. His Lordship would appear therefore also to have been of opinion that the freedom guaranteed by s. 92 is a personal right. (at p284)

47. It is now settled, I think, after some fluctuation in opinion, that s. 92 is an inhibition addressed to the Parliaments of the Commonwealth and the States preventing them from legislating so as to interfere with the freedom prescribed by the section. It gives no rights to the citizens of the Commonwealth except the right to ignore and if necessary to procure the assistance of the judicial power in resisting any such legislation (James v. South Australia (1927) 40 CLR 1, at p 31 ; James v. The Commonwealth (1939) 62 CLR 339, at pp 361, 362 ; James v. The Commonwealth (1936) AC 578; 55 CLR 1 ). Still the freedom is not limited "to freedom from legislative control; it must equally include executive control" (James v. The Commonwealth (1936) AC 578, at p 628; 55 CLR, at p 56 ). But, doubtless, the expression trade, commerce and intercourse "describes the activities of individuals. The object of s. 92 is to enable individuals to conduct their commercial dealings and their personal intercourse with one another independently of State boundaries" (O. Gilpin Ltd. v. Commissioner for Road Transport and Tramways (N.S.W.) (1935) 52 CLR 189, at p 211 ). It was said, however, that s. 92 relates only to the passage of goods or visible tangible things and persons across the borders of the States and is wholly inapplicable to intangible things or commercial intercourse across State borders. And it was claimed that the addition of the words "whether by means of internal carriage or ocean navigation" in s. 92 supported this view. And so, also, it was claimed that the opinion of the Judicial Committee in James v. The Commonwealth (1936) AC 578; 55 CLR 1 was based upon this assumption. (at p305)

Cole v Whitfield

“After a long series of cases failed satisfactorily to resolve the meaning of this provision, the HCA, in a rare unanimous judgment, revised the law radically following a careful historical analysis of the framers’ intentions and understandings of the free trade principle.” “Particularly prominent example of this historical method, but the method is well- established. However, this use of historical method does not amount to a full-blown commitment to ‘originalism’ in constitutional interpretation. Most members of the Court have been clear that the Constitution’s meaning changes over time and that its ‘original meaning’ may not govern the present.”

“Moreover, there is some disagreement about the precise uses to which history is put. While historical material may be used as evidence of the intention of its framers on some occasions it is used it in other ways: to identify the historical understanding of the text at the time of its drafting (a separate idea from the framers’ intention) or to identify historical practices that inform the meaning of the Constitution.” The departure from individual rights to a law offends s 92 if it imposes ‘discriminatory burdens of a protectionist kind’ or if its effect is ‘discriminatory against interstate trade and commerce in that protectionist sense’ or ‘if its effect is discriminatory and the discrimination is upon protectionist grounds’

8 pages.